The Gift of Life

In late summer 2019, Danielle Cannon was on her way to work in Hickory, NC, when a passing SUV drew her attention. A sign on the vehicle read, “My Dad needs a kidney. Please call this number.”

Danielle thought to herself, “I could totally do that.”

And she did.

She didn’t call that number, but by the end of the following summer, Danielle had given her kidney to a UVA Health patient—someone she’d never met.

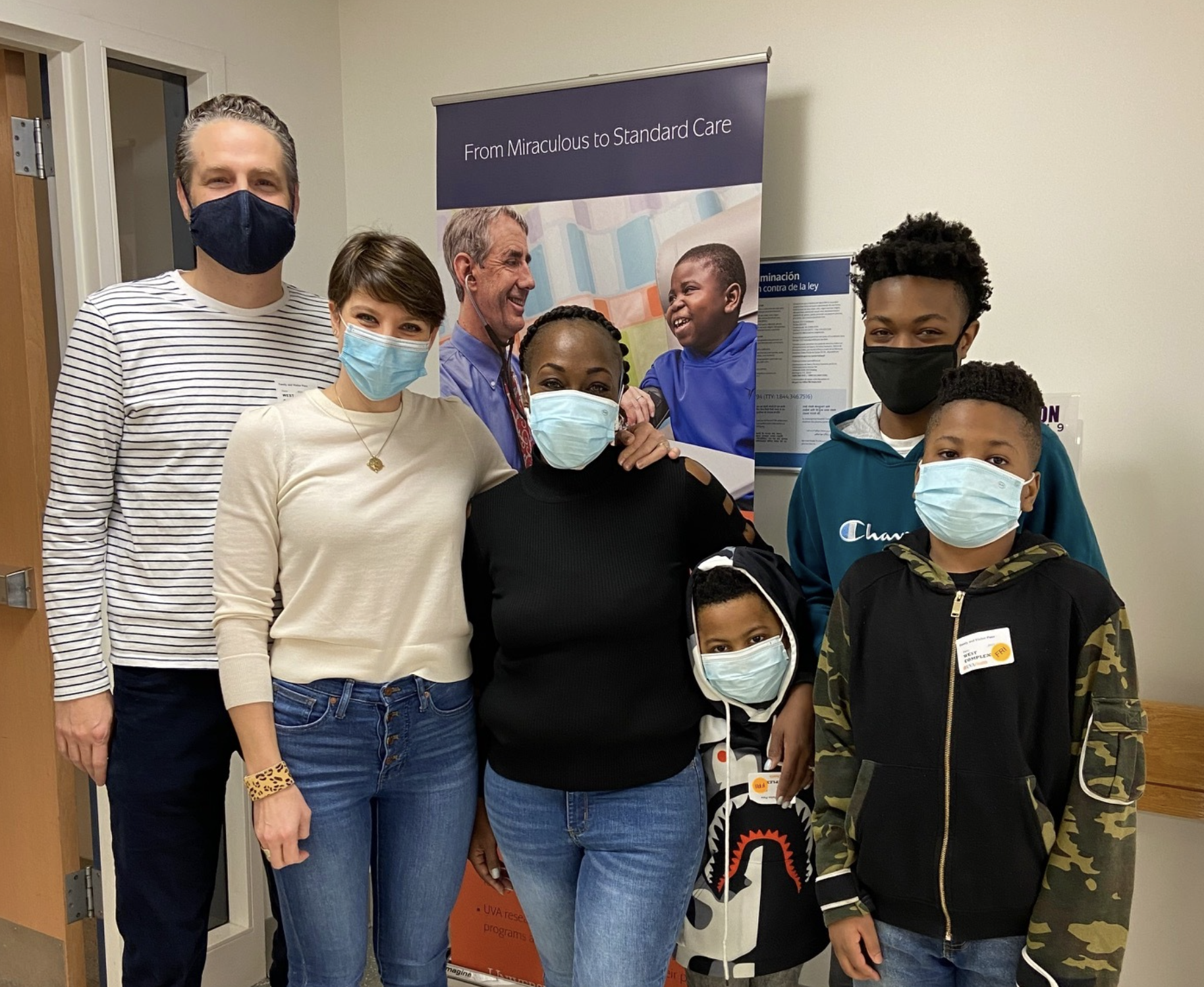

Danielle has since met the recipient, Melissa Booker, a Charlottesville mother of four boys who works as a registered medical assistant and certified nursing assistant. The two have become friends. It’s just one of the many positive outcomes of Danielle’s fast and eventful journey to living organ donation. She’s also become a strong advocate for and financial supporter of UVA Health’s Living Organ Donation program. Recently, she and her husband, Kit, designated a gift in their estate plans to create, or if already created, contribute to, a named endowed fund called the Living Organ Donation Fund for the benefit of the Charles O. Strickler Transplant Center at UVA Health University Medical Center.

WHAT IS LIVING ORGAN DONATION?

Living kidney donors give one of their two functioning kidneys to a patient with end-stage kidney disease. UVA Health performs 35 living kidney donations per year on average.

According to nurse practitioner Anita Sites, the lead clinician and manager of UVA Health’s Living Organ Donation program, approximately 90,000 people with end-stage kidney disease are on the waiting list for a transplant in the United States. That figure excludes thousands more adults and children with kidney disease or failure who may be candidates for a new kidney imminently. The average wait time to match with a kidney from a deceased donor is three to five years.

“There simply aren’t enough deceased donor organs to supply all the people in need,” said Anita. “Living organ donation developed out of necessity to find more organs, but over the years, it’s been shown that kidneys from living donors are superior in a lot of ways.”

Compared to an organ from a deceased donor, kidneys from living donors start working faster and last longer. A significant added benefit of living donor transplants is advanced planning and scheduling.

Anita said more people are learning about living organ donation thanks to social media and medical shows like “Grey’s Anatomy.” Still, living donors who give without knowing the recipient’s identity (often called non-directed, anonymous, or altruistic donors) are rare. On average, four of approximately 35 annual living kidney donations performed by UVA Health are from anonymous donors like Danielle.

“I just felt called to do it,” said Danielle. “Our health is everything. I’ve been very fortunate in my life in so many ways, and not everybody has that. Also, I’ve had a lot of surgeries over the years, I recover well, and I’m not skittish around needles.”

By January 2020, she was ready. Danielle began contacting living organ donor programs at nearby health systems in North Carolina. Then she shared her decision with her husband, her boss, a few friends, and one family member—a niece living outside Richmond. With her intention out in the world, an opportunity soon presented itself, but in another state.

Danielle’s niece told her about a Facebook post she’d seen from a friend in Virginia. The friend’s 9-year-old daughter, a UVA Health Children’s patient, needed a kidney from a donor with type A blood under the age of 50.

Danielle thought, “That’s me!” and immediately contacted UVA Health about becoming the little girl’s donor. That put her in touch with Anita and launched a lengthy evaluation and consultation process.

“We make a decision about someone's living donation candidacy, but they decide whether they’re truly going to move forward or not, and I think that's a pretty big leap of faith, especially for a non-directed donor,” said Anita.

Danielle’s leap of faith included many blood tests, physical and mental health screenings, and meetings with UVA Health’s transplant coordinators, social workers, and psychologists. Anita and her team diligently worked to determine if Danielle was physically capable of donating and had a clear understanding of and ability to manage living with one kidney.

Finally, in June 2020, Danielle’s candidacy was approved. However, as it turned out, she was not a match for the little girl on Facebook (who received a kidney from someone else).

At that point, Danielle had to make a choice. One option was finding a recipient closer to home in North Carolina. By then, however, she felt so comfortable with UVA Health’s level of care, communication, and concern, and especially with Anita, whom she calls her guardian angel, that she said, “I’m giving y’all a kidney. You just find someone who needs it.”

A month later, she received the call. There was a match.

A LIFELONG CONNECTION

The surgery was scheduled for early August, and Danielle had to break the news to her mom and dad. Understandably, they had concerns.

“They hemmed and hawed, but I knew the answer to every question they had,” said Danielle. Still, her mom remained skeptical and worried. “My mom is so giving and always volunteering,” said Danielle.

“I finally told her, ‘I get this from you!’ and she couldn’t argue with that.”

Ultimately, Danielle’s mother became a strong supporter and accompanied Danielle and Kit to UVA Health University Medical Center for the donation surgery. Danielle said she felt like a VIP in the hospital. “It was the highest level of care that anyone receiving a medical procedure could hope for.”

According to Anita, living donors deserve special treatment. “Living donors are the most special patients in the world. Donating a kidney, especially to a stranger, is extraordinary.”

After Danielle’s donation, there were several more trips back and forth to Charlottesville for post-op care. Then, after three months, she was able to meet the recipient. Anita’s team facilitates contact between a donor and recipient after a 12-week recovery period if both parties are amenable. Because of the pandemic, Anita arranged for a Zoom meeting. She and UVA Health social worker Emily Lyster, LCSW, joined the video chat.

“As soon as Melissa came on the screen, we all just cried,” said Danielle.

Eventually, the two got together in person, which Melissa called “a beautiful experience.”

“I was so nervous the night before,” said Melissa. “What do you give to someone who has given you a second chance at life?”

She chose to give Danielle a necklace with a single angel wing. Melissa has a corresponding wing and said she never takes it off.

Although Melissa had been managing health issues related to pregnancy complications for years, she had learned only two months before the transplant that she’d have to go on kidney dialysis several hours a day, several days a week, until a new kidney could be found—likely, in three to five years.

Thanks to a bit of serendipity and a lot of passion and perseverance on Danielle’s part, that timeframe was drastically reduced.

“From the moment I met Danielle, I could tell she was committed to the cause,” said Anita. “She was an excellent patient, and she is a powerful advocate for living organ donation.”

GRATITUDE AND GENEROSITY

Danielle’s estate gift to the Transplant Center will make it easier for others to do what she did.

“I feel so passionate about living organ donation that I would do it again tomorrow. I would do it every five years if I could,” said Danielle.

Speaking on behalf of her husband, Kit, she added, “We feel so fortunate about our experience with Anita. We want others to have the same opportunity, and we don’t want financial constraints to be an objection. We want more people to see that sign on a vehicle or something on social media and be moved to help.”

A special Medicare provision generally covers the cost of a living organ donor’s medical evaluation, surgery, and aftercare, and UVA Health helps living donors access resources for travel expenses and lost wages. Still, there are many gaps and disparities that deter living donation. Philanthropy can be the difference between a person becoming a living donor or not.

Beyond patient support, Anita said philanthropic funds can help raise public awareness and understanding of living organ donations.

“There are a lot of misconceptions. We want to grow our program because of the amazing outcomes, but it requires educating the community that living donation is an option. A lot of people don't know it can be done safely,” said Anita.

“There's no greater gift than literally giving a piece of yourself entirely for the good of someone else. And to do that for a stranger you might never get to meet is truly special. That's why it’s so meaningful to work with patients like Danielle.”