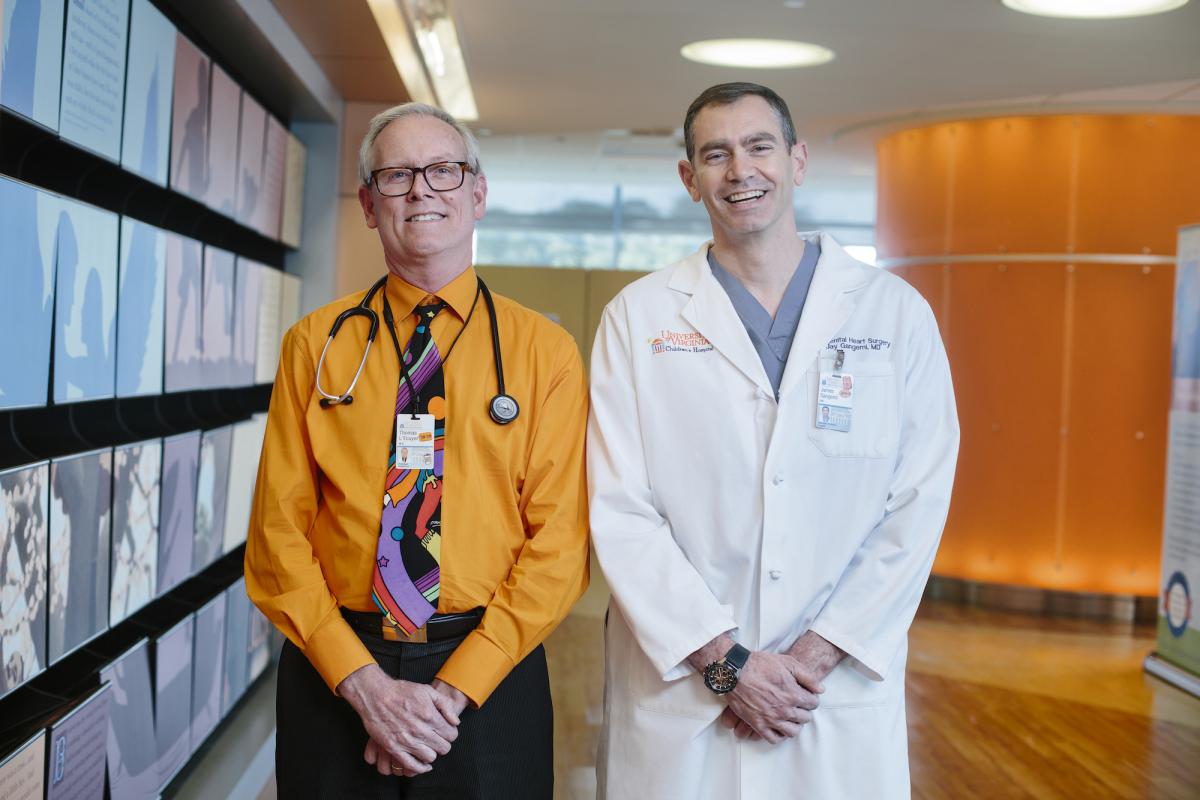

For This Pediatric Duo, It’s All About The Team

It’s 4:45 a.m., and James Gangemi is starting his day: exercise, breakfast, and then he’s off to work. The routine sounds typical, but the situations he encounters on the job couldn’t be more unique.

That’s because his office is an operating room, and his clients are children who need congenital heart surgery, some of whom are on the brink of heart failure. As director of pediatric cardiothoracic surgery, James Gangemi is part of a team that performed 13 pediatric heart transplants in 2018. While that is an astounding number for a hospital of UVA’s size, the program’s success and accolades, Gangemi says, are the result of teamwork.

“Transplant medicine is the epitome of a high-functioning team, and our team is always prepared, we have a tremendous work ethic, and there are no egos here—everyone is important,” Gangemi says.

One of those important people who works hand-in-hand with Gangemi is Thomas L’Ecuyer, a pediatric cardiologist and medical director of pediatric heart failure and transplant. Before a surgery is deemed necessary and the flurry of coordination begins, a network of doctors and nurses are working behind the scenes to investigate and diagnose the most life-threatening cases.

This is where L’Ecuyer lends his expertise. Because UVA is the only hospital in Virginia that performs pediatric heart transplants, L’Ecuyer is in constant communication with pediatric cardiologists throughout the Commonwealth.

When a child is ultimately referred to L’Ecuyer, he follows a two-step mental process. First, he wants to exhaust any other existing therapies that could possibly help the child recover. However, if it’s determined that the child does, in fact, need a heart transplant, then L’Ecuyer moves to step two: rapidly determine if the child has any conditions that make transplant a poor option, register the child for transplant as quickly as possible, and then take precautions that will maximize the child’s chances of survival until transplant.

Among others, these precautions include treating the patient for their existing heart failure, optimizing their nutrition, and admitting the patient to the hospital when heart failure worsens to increase support and elevate their status on the waitlist. U.S. News & World Report ranks UVA among the top 50 hospitals in the country for pediatric cardiology and heart surgery, and last year the team performed nearly 300 total heart-related procedures, 46 of which were on babies 30 days old or younger.

In such a high-stakes field that demands an incredible amount of specialized skill, it would be natural to think Gangemi and L’Ecuyer are primarily nervous about executing the technical aspect of their jobs. But it’s more complicated than that. Confident in their training, ability, and peers, it’s actually the emotional gravity of the situations that weighs the heaviest.

“Once we get the child listed, it’s the waiting that’s the hardest part for me,” L’Ecuyer says. “Because even when I know a child needs a transplant, I can’t honestly tell the parents that the surgery will happen because we have to wait for a donor.”

Similarly, Gangemi places a great deal of importance on communicating with, and having a sense of empathy for, the family.

“When I’m in the operating room, I’m so focused on the procedure that I don’t think about anything else,” he says. “But beforehand, when I’m with the parents, I’m very open with them. I ask about their concerns, about their fears, and as a parent myself I can understand a small piece of what they’re going through.”

“I always say that when I became a dad, I became a better doctor,” Gangemi adds.

At the core of this team is an immense feeling of ownership and responsibility, an understanding that, in a sense, the young people they’re caring for are their own. And the elation they experience when the child pulls through—Gangemi and L’Ecuyer say that language simply doesn’t do it justice.

L’Ecuyer recalls a recent child who required life support from an ECMO machine (which pumps and oxygenates a patient's blood outside the body, allowing the heart and lungs to rest) for three months after transplant.

“We were very concerned about whether she could survive this period, but she did,” L’Ecuyer says with a smile. “It’s a fantastic feeling. When people come to you without much hope, it feels great to give them hope back.”

As for the future of pediatric heart transplant at UVA, Gangemi sees nothing but potential.

“What we have here is pretty unbelievable in terms of the care and outcomes the patients get,” Gangemi says. “The way we work together is great, families are satisfied, and the team gets to share that."