'Research Saved My Life'

Kristin Anderson, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Cancer Biology at UVA School of Medicine, was a graduate student when she was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive breast cancer.

“I immediately went home, opened my graduate-level cancer biology textbook, and looked up survival rates for patients with triple-negative breast cancer and a BRCA1 gene mutation. It was terrifying,” said Anderson.

At the time, Anderson said her boyfriend (now husband), a fellow scientist, told her, “‘Don’t freak out. You’re not a number. You’re a person. We caught it early, and you’re going to get through this.’”

And she did. But Anderson’s experience as a person with cancer continues to influence her work as a cancer researcher, and it drives her motivation to develop more precise and personalized therapies for cancer patients.

“Research saved my life. The reason I had the successful outcome I did was because people—scientists and clinicians—put time and effort into learning how to treat my type of cancer more effectively,” said Anderson.

“One of the things I’m trying to train the next generation of researchers in my lab to do is follow the science while continually pivoting back to the most relevant patient-centered questions,” she said.

The Anderson Lab studies how to engineer T cells (immune cells) to recognize and kill solid tumor cancers that are often diagnosed at a late stage and particularly difficult to treat. Although Anderson is a laboratory-based scientist, her work directly translates to patient care. Her goal is to build tools that can be developed into new immune-based therapies, which are more targeted and less invasive than other cancer treatments. In some cases, immune-based therapies can be combined with conventional treatments (chemotherapy, radiation, surgery) to improve efficiency and lessen side effects. One of the Anderson lab’s primary foci is ovarian cancer, the research on which has been underfunded relative to other cancers.

“Not enough people are doing this work. The more we study, the more questions we come up with, because so many haven’t been answered yet,” she said.

Anderson was a postdoctoral researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle before starting her independent lab at UVA School of Medicine and joining the Beirne B. Carter Center for Immunology Research. She was successfully recruited thanks in part to support from the Rodger W. Klein Family Fund at UVA Cancer Center.

Speaking on behalf of the Klein family, Allison Klein (Rodger's daughter) said, “Our goal in creating the endowed fund was to give the director of UVA Cancer Center the discretion to fuel promising cancer research focused on immunotherapy and genomics. We couldn’t be more pleased that it helped recruit Kristin Anderson to UVA to investigate and address a critical gap in care for ovarian cancers.”

A FAMILY’S LEGACY

Klein, who lives in Wilmington, NC, is a triple-negative breast cancer survivor herself. After being blindsided by her diagnosis in 2023, Klein sought treatment at UVA Cancer Care from an interdisciplinary team that included breast cancer surgeon Shayna L. Showalter, MD, and oncologist Trish Millard, MD.

Together, the doctors recommended a multipronged treatment protocol combining chemotherapy, surgery, radiation, and immunotherapy.

“It brought me comfort to know we were hitting the disease with more than one thing,” said Klein. “I felt good about the treatment plan and my care team. Having cancer can feel like you’re on a runaway train with no control, but Dr. Showalter and Dr. Millard empowered me to make choices about my care while guiding me, supporting me, and cheering me on. And now I’m at a stage where there is zero evidence of disease.”

Like Anderson, Klein understands that years of research went into developing the tools and treatments she depended on. One of those tools was a groundbreaking immunotherapy called Keytruda, which works by blocking a protein that cancer cells use to evade the immune system, thus boosting the ability of the patient’s T cells to detect and kill the cancer cells.

“At some point, researchers began investigating the science, and other people funded that early research and the development and testing of a new medication that potentially saved my life,” said Klein. “And they did that with no guarantees. There's never a guarantee that something safe and effective will be developed or developed quickly. But every bit, every step gets us closer to more personalized care and better outcomes for cancer patients and their families.”

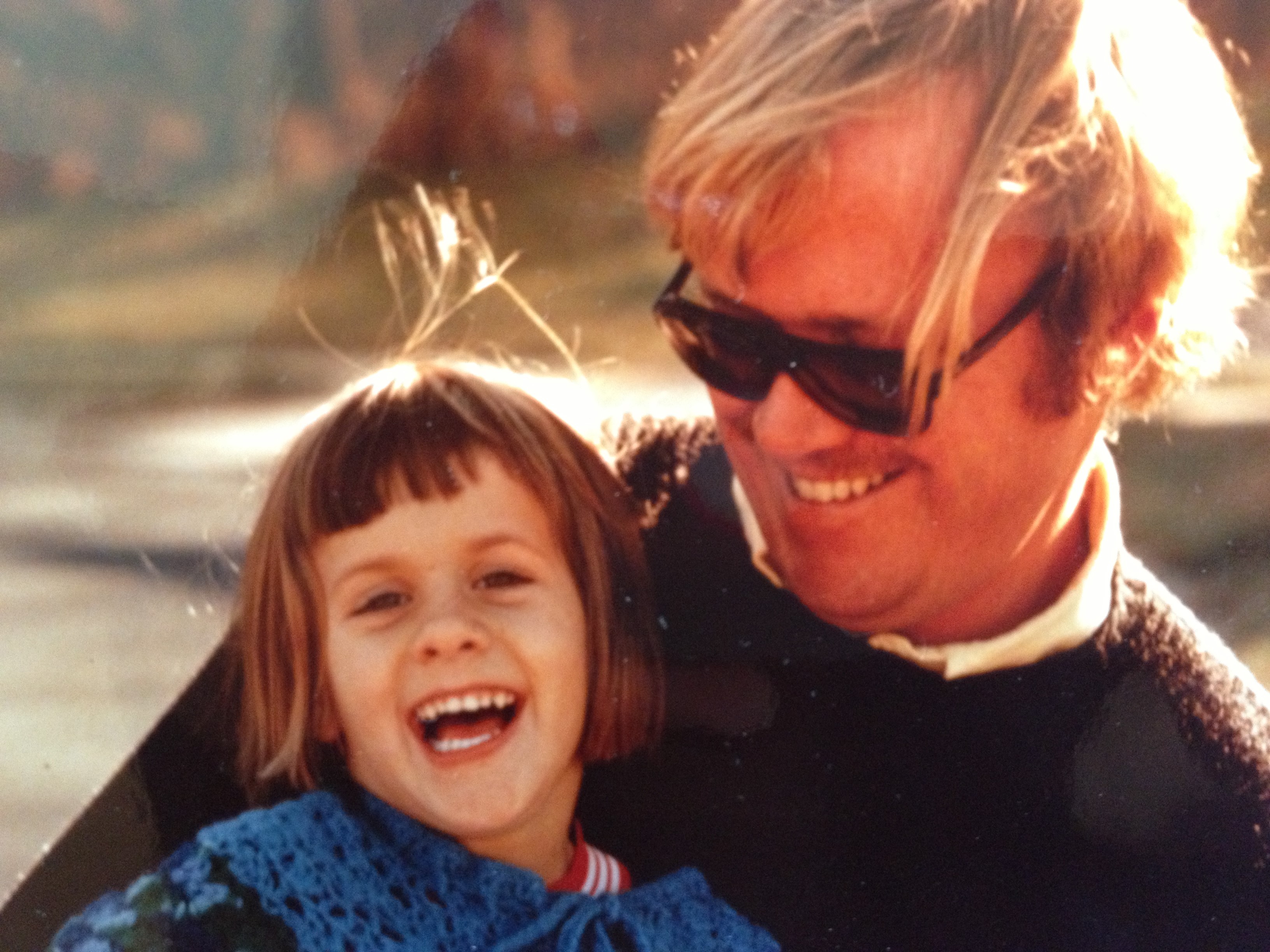

In the case of Klein’s father, Rodger, a UVA School of Law alum for whom the family’s endowed fund is named, a little bit meant a lot after he was diagnosed in 1980 with advanced biliary duct cancer that had metastasized to his liver.

“By the time he was diagnosed, my dad was told he had between two weeks and two months to live. He’d just turned 42,” said Klein. “His only option was to enroll in a clinical trial for an experimental targeted cellular therapy at Johns Hopkins. The treatment was so experimental, it could kill him before the cancer could, but he said, ‘Sign me up.’”

Because of that decision, Rodger lived for another year and a half.

“He knew he was on borrowed time,” said Klein, “and he believed the trial could lead to something bigger. For the most part, he had a good quality of life during that year and a half. He went back to work. We took a long family vacation that summer. I'm sure that time was incredibly precious to him.”

COMING FULL CIRCLE

Anderson is in the process of applying for funding for a new clinical trial that will test the safety and efficacy of an ovarian cancer immune therapy she’s been studying in the lab for years.

“If it goes well—if we get promising preliminary data and everything is safe—we’ll apply for more funding to scale it up for more patients,” Anderson said.

Anderson is also collaborating with other cancer scientists and clinicians at UVA Cancer Center and beyond to help develop immune-based therapies for patients with other hard-to-treat cancers, including glioblastoma, melanoma, and pancreatic and cervical cancers.

“I’m excited about Kristin’s research and its potential to address cancers that are diagnosed late and hard to treat, like my dad’s,” said Klein. “There's been so much success in finding new and better ways to treat many types of cancers, and I’m just itching to get those next breakthroughs for patients with cancers that are much harder to fight.

"After what my dad went through and my own battle with triple-negative breast cancer, supporting this work feels very full circle to me."