This UVA Physician is Finding New Cures with Old Drugs

It has been called a silent epidemic. Age-related macular degeneration affects more than 10 million Americans and is one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide. As our population ages, the numbers will continue to climb at an alarming rate.

The impact on public health could be devastating. A UVA professor believes he can begin to turn this trend around.

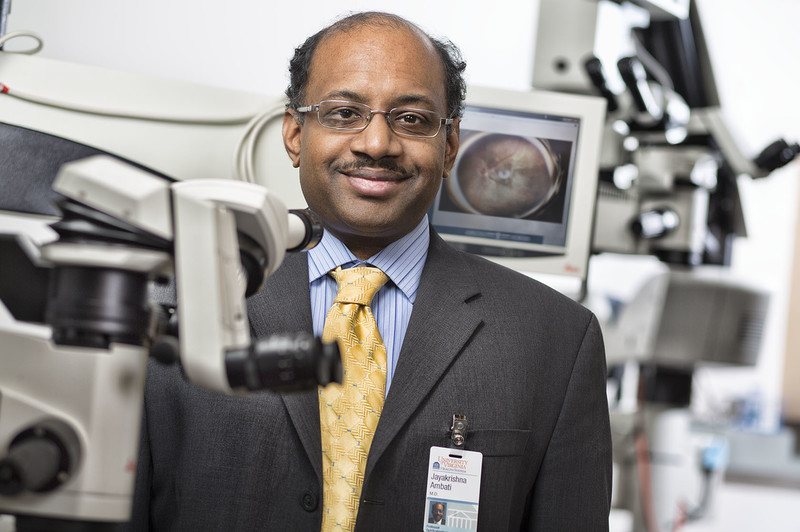

“Drug approvals by the FDA—not just for macular degeneration, but for other illnesses as well—are dropping while more people are getting sick every year. It’s a clarion call. We have to change how we search for new treatments and how quickly we can get these therapies to patients,” says Jayakrishna Ambati, MD, the DuPont Guerry III Professor of Ophthalmology and director of the Center for Advanced Vision Science.

Ambati leads UVA’s efforts to develop therapies that will stop the progression of macular degeneration and restore patients to a normal life. Recently, he and his team discovered a class of HIV-fighting drugs that have the potential to combat not only macular degeneration but also type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and atherosclerosis. A modified, less toxic version of this drug soon will be in clinical trials to test its effectiveness against macular degeneration.

“It was truly serendipitous that we found this compound,” Ambati explains. “Sometimes drugs possess unknown and unexpected disease-preventing properties. These properties are just waiting to be discovered.”

A “BOOM OR BUST” APPROACH

The cost to develop new drugs and acquire FDA approval is staggering. It takes, on average, 12 years for a new drug to reach the market at a cost of $2.6 billion. Over the past six years, just nine drugs achieved FDA approval for ophthalmic treatment and only five were new drugs. A new approach is desperately needed.

Ambati has assembled a team of clinicians, basic science researchers, statisticians, computer scientists, and data scientists from across Grounds to develop a systematic approach to identify all drugs that could be repurposed for other diseases. The team is collaborating with other groups across the country to create an algorithm that searches through multiple, independent medical databases. Results are studied over time across different locations and age groups. A new drug candidate must show evidence of its potential to prevent disease in every database before it is considered as a potential therapy for previously unimagined disorders.

“Our work reveals these interactions hiding amongst large healthcare databases,” he says. “It’s Big Data archaeology.” Repurposing existing drugs, and resurrecting those drugs that have been abandoned in the long approval process, allows researchers to “short circuit” the costly and time-consuming steps in the drug development process.

“What would it take to profoundly impact human vision?” Ambati asks. “Finding just one new drug of sufficient size, scope, and robustness could change how we care for blindness for years to come.”