Breaking the Dam

Since UVA neuroscientists discovered the link between the brain and the immune system in 2015, researchers across UVA Health and worldwide have been investigating ways of leveraging this connection to treat neurologic diseases and disorders from autism to Alzheimer’s. At UVA, private donors and foundations have fueled groundbreaking discoveries in this area. The research team of Scott Zeitlin, PhD, an associate professor of neuroscience at UVA School of Medicine, recently benefited from this generosity.

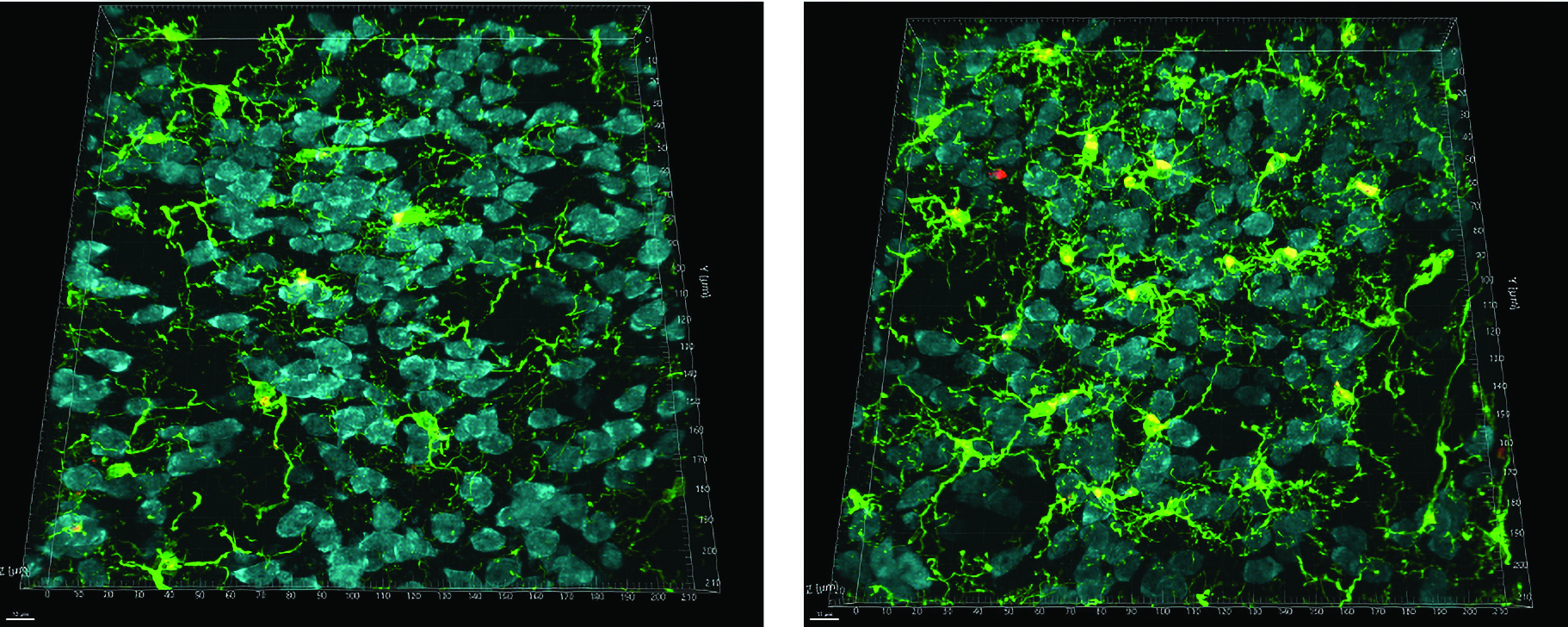

With visionary support from the Pelican Fund, Zeitlin and his team are uncovering the secrets of Huntington’s disease (HD) and identifying new targets for combating this debilitating, fatal brain disorder. His experiments are illuminating (literally with fluorescent dye in some cases) how the body’s innate immune responses are implicated in HD and can be harnessed to delay and mitigate HD symptoms. Beyond giving new hope to families affected by HD, Zeitlin’s findings may open the floodgates for new treatments for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and more.

THE MYSTERY OF HUNTINGTON’S

HD causes the progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. It results from a mutation in the huntingtin gene, which is passed down within families from generation to generation. Children of parents with HD have a 50% chance of inheriting it, but symptoms typically don’t develop until adulthood. The Huntington’s Disease Society of America (HDSA) estimates today that 41,000 Americans are HD symptomatic and another 200,000 are at risk of inheriting the disease. Symptoms of HD include personality changes, impaired memory and judgment, unsteady and involuntary movements, slurred speech, swallowing difficulties, and substantial weight loss. It’s like having ALS, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s simultaneously, according to the HDSA. Eventually, HD symptoms advance to a stage where those afflicted can no longer care for themselves. Most people with HD succumb to complications within 10 to 25 years of symptom onset.

Currently, there is no cure or treatment for HD—nothing to slow, stop, or reverse its progression; however, after a Columbia University geneticist and neuropsychiatrist named Nancy Wexler led the discovery of the huntingtin gene in 1993, excitement has grown that novel therapies are imminent. Zeitlin, who joined UVA School of Medicine in 2000, has been on the front lines of that search since Wexler recruited him to study HD as a postdoc at Columbia.

“Nancy Wexler has HD in the family, and she, herself, has it. At the time, she really wanted mouse models of the disease, and I thought that was really cool,” said Zeitlin.

Mouse models—mice developed or engineered to simulate human diseases—allow scientists to study those diseases in a lab. Zeitlin created the mouse models used by most labs investigating HD today. In 2019, he received the Hereditary Disease Foundation’s Leslie Gehry Prize for Innovation in Science. Zeitlin credits Wexler’s ability to motivate people to work on a common problem for the increased understanding and study of HD.

“People think science happens because there are a lot of labs, and they’re working hard on a problem, and there’s a eureka moment,” said Zeitlin. “But what I think drives science are certain individuals, like Nancy Wexler, who can be very, very persuasive and convince others to work on the same problem as a research community—to share information and resources instead of compete with each other.”

As a research community, Zeitlin and his neuroscience colleagues at UVA are those people, too, and combined, they are poised to make exceptional progress in understanding and treating many neurodegenerative diseases and neurodevelopmental disorders, individually and collectively. And it all started with that landmark 2015 discovery.

LEVERAGING THE MISSING LINK

When UVA researchers made the revolutionary connection between the brain and the body’s immune system, it was by uncovering a network of lymphatic vessels no one knew existed. These newly identified vessels surrounding the brain—meningeal lymphatics—send messages between the brain and the immune system and clean the brain of harmful materials. This discovery was a radical scientific leap, causing textbooks to be rewritten. It also created new possibilities for understanding and treating many brain diseases and disorders. Since then, UVA Health has substantially advanced a new field of science called neuroimmunology.

UVA’s pioneering researchers are not only investigating the intersection of neuroscience and immunology on an individual disease and disorder level but also collaborating to make collective progress. UVA’s Center for Brain Immunology & Glia (BIG), of which Zeitlin is a member, is a manifestation of this fertile ground on UVA Grounds. Other members of the center include neuroscientists studying Alzheimer’s, ALS, Parkinson’s, and multiple sclerosis, as well as those exploring toxoplasmosis, autism spectrum disorder, strokes, epilepsy, glioblastoma, and depression. The BIG center is a genuine brain trust from which member researchers can draw valuable transferable insights, enabling them to advance science in their individual interest areas faster.

The work of BIG center members is further amplified by UVA’s Brain Institute, a University-wide initiative established in 2016 to invest in and foster closer collaboration among neuroscientists like Zeitlin, who study the brain and its diseases and disorders in the lab, and those who conduct clinical trials of new medicines and treatments based on that research. In addition, the Harrison Family Translational Research Center in Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases, which will be housed in UVA’s new Paul and Diane Manning Institute of Biotechnology, will enable the rapid manufacturing and testing of those new therapies, making the laboratoryto- bedside pipeline even shorter. Construction of the institute is expected to be completed by late 2026.

The three experimental research projects the Pelican Fund supports in Zeitlin’s lab are primed to benefit from UVA’s robust and growing neuroscience infrastructure. They include:

1. Using fluorescent tracers (dye) to study how fluid drainage through the meningeal lymphatics is implicated in HD;

2. Studying the role of brain microglia (immune cells of the central nervous system) in HD;

3. Investigating HD’s connection to inflammasome activation, a function of the innate immune system that senses damage in the brain and triggers an inflammatory response.

Notably, the Pelican Fund’s support enabled Zeitlin to hire a postdoctoral research fellow who brings vital experience with microglia and neuroinflammation from previously working in the lab of Ukpong Eyo, PhD, a fellow BIG center member. Eyo studies the connections among microglial activity, neurodevelopment, and neurodevelopmental disorders.

“We would not have conceived of or considered looking at the meningeal lymphatics system in the context of HD in mouse models unless we had the in-house expertise of other labs,” said Zeitlin. “It really is critical that you have enough people with expertise around in your immediate environment. That makes the research go much, much quicker.”

SUPPORT FOR TESTING THE WATERS

Funding for highly experimental laboratory studies is also critical to making discoveries happen more quickly. The generosity of UVA School of Medicine donors like the Pelican Fund accelerates science by allowing researchers to conduct high-risk/high-reward investigations that generate the necessary data to receive extensive, sustaining grants from federal funders, namely, the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—grants that facilitate more expansive preclinical and clinical studies and lead, in turn, to more effective therapeutics.

Private support continues to be crucial even when a lab has received an NIH grant because the use of those funds is so limited. “People may not realize that the NIH only allows you to spend money on certain things. So we can’t, for example, buy computer systems for imaging analysis. They won’t allow their funds to be used for purchasing software,” said Zeitlin. “But because of the Pelican Fund’s support, we were able to get an imaging analysis system in the lab to allow us to quantify all the data we’re getting in those three projects, which has been terrific.”

Something else the NIH doesn’t fund? “Paper towels,” said Zeitlin. “It’s true; I mean, you’d think that things would be set up better for science. But no.” To the uninitiated, paper towels might not seem like serious science tools, but for wet labs, they’re an essential resource. In other words, by closing gaps in financial support for Zeitlin’s day-to-day operational needs, including staffing, equipment, and, yes, paper towels, the Pelican Fund is helping advance the understanding and treatment of HD. Without reliable funding for seemingly mundane but critical elements like these, many significant research discoveries would be thwarted or delayed.

HOPE FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES

Zeitlin said the research is still at an early stage, but he hopes to identify promising targets for HD therapies to “push out the actual onset of symptoms until individuals are very, very old so they have a much longer period of high-quality life.” That’s excellent news for those affected by HD and any brain disorders with underlying mechanisms connected to similar innate immune system pathways. “I think if the field can find a cure for HD, it will break the dam for many other neurodegenerative diseases,” said Zeitlin.

To learn more about how you can support Scott Zeitlin’s groundbreaking research and accelerate

treatments for tomorrow’s patients, please contact Kelly Reinhardt, Director of Development,

Neurosciences, at ksr2h@uvahealth.org or 434.962.6671, or call 800.297.0102.